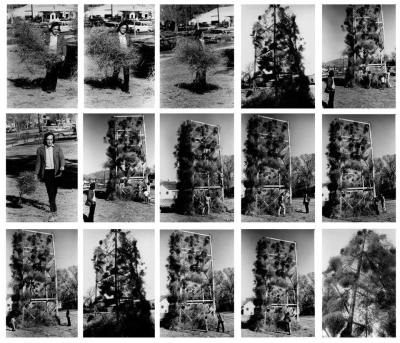

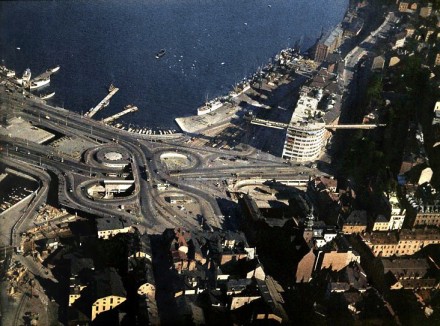

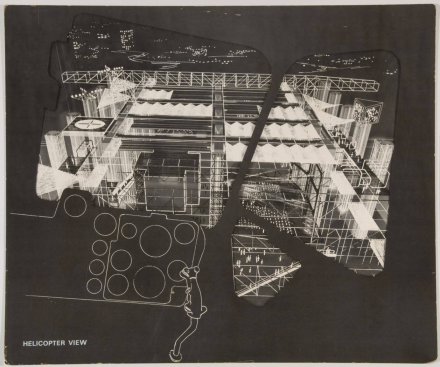

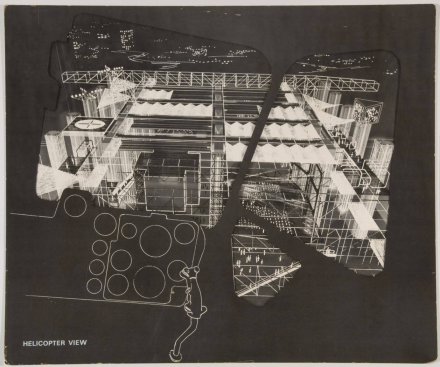

Helicopter view, c. 1964. Image from the Cedric Price Archive at the CCA (The Canadian Centre for Architecture)

Helicopter view, c. 1964. Image from the Cedric Price Archive at the CCA (The Canadian Centre for Architecture)

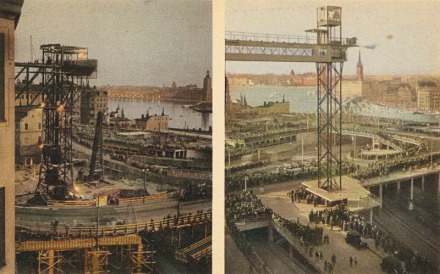

Image from the Cedric Price Archive at the CCA (The Canadian Centre for Architecture)

Image from the Cedric Price Archive at the CCA (The Canadian Centre for Architecture)

“Choose what you want to do – or watch someone else doing it. Learn how to handle tools, paint, babies, machinery, or just listen to your favourite tune. Dance, talk or be lifted up to where you can see how other people make things work. Sit out over space with a drink and tune in to what’s happening elsewhere in the city. Try starting a riot or beginning a painting – or just lie back and stare at the sky.”

Fun Palace: Promotional brochure, Joan Littlewood, 1964

There is very little to be said about the Fun Palace, the cybernetic and unrealised gesamtkunstwerk planned between 1961 and 1965 by theatre impresario Joan Littlewood and Cedric Price, that has not already been said or suggested elsewhere. As an avant-garde architectural mongrel, crossing divisions between theatre and structure, static and dynamic, breaking with the temporal logics of the classical architectural object, weaving the social sphere together with cultural production, aesthetics and functionality in an ever-changing system of constant creativity, bridging labour and leisure in a unit of pleasurable productivity, the project has become the standard reference for any architect and architecture in search for a new avant-garde, struggling for an oppositional position, for degrees of freedom and attempting to formulate architectural alternatives.

The division between work and leisure has never been more than a convenient generalisation used in summarising conscious human activity – voluntary and imposed. Both the nature and the scale of conditions causing or requiring imposed activity have changed to such a great extent over the past 25 years that even the convenience of such a division is no longer acceptable

The present socio/political talk of increased leisure makes both a slovenly and dangerous assumption that people on the one hand are still sufficiently numb or servile to accept that the period during which they earn money can be little more than made mentally hygienically bearable and that a new mentality is awakened during periods of self-willed activity. Increase in wealth, increasing personal mobility, flexibility of labour and decreasing essential social interdependence are some of the constituents of the change rather than the cause.

Argument for Fun Palace by Joan Littlewood and Cedric Price. Presented in TDR (The drama review), vol 12, number 3, spring 1968. pp. 128

Cedric Price’s oeuvre is one of a multitude of dimensions, layers and implications, but could maybe be (over)simplified – in parallel to several of his contemporaries – as a critical inquiry into the temporal finality of the building and the architectural system (as and in its various institutions) as a Foucauldian mechanism for the consolidation of power and authority. Presented as a counterproposal, promoting freedom and emancipation as an architectural priority, Price, often in cross-disciplinary collaborations, developed and introduced concepts such as non-plan, plug-in, self-organisation, cybernetics, system, open-endedness, adaptability and indeterminacy as architectural principles and in the professional discourse. At the Fun Palace those ideas manifested themselves in a large membrane roof, suspended over an interlocking service grid in which rows of functional (stairs, elevators etc) towers divided the space into smaller environments. To make able the plug-in and plug-out of flexible components, a system of gantries where suggested to hover above the free space, leaving no possible configuration of the “laboratory of pleasure” unturned. In historical reference with, for example, J.N.L Durand, Peter Behrens (AEG), Le Corbusier (Maison Dom-ino), and Mies van der Rohe (Universal space) the exterior and outside of the Fun Palace attached to its surroundings as a generic, anonymous and systemic structure. Even though a couple of London sites where considered as potential locations, the Palace rejected a traditional sense of place and expressive material belonging, instead its connections to the surrounding city, its inhabitants and urban fabric took place at a level of internal performativity, activity and mental situé. Or, in the more precise words of Stanley Mathews, as an attempt to generate a ‘matrix that enclosed an interactive machine… a vast social experiment in new ways of building, thinking and being’ (Stanley Mathews, From Agit-Prop to Free Space: The Architecture of Cedric Price, 2007).

The increasingly obvious reduction of the permanence of many institutions – obvious within a decade rather than, as previously, from generation to generation – allied with the mass availability of all means of communication, have demanded an almost subconscious awareness of the vast range of influences and experiences open to all at all times.

This dimension of awareness enables a questioning by all of existing facilities available in, say, a metropolis – not merely in an assessment of physical or measurable limitations. The city today works in a constipated way, in spite of its physical and architectural limitations. The legacy of redundant buildings and the resultant use patterns acts as straitjacket to total use and enjoyment. A problem of re-planning the city is one of scrapping and adapting the existing forms to enable this fuller, more random and sophisticated use of urban facilities, while ensuring that any new work will not in its turn create an inappropriate physical discipline in the future.

Not all buildings or roadways can be built to collapse or disintegrate by the end of the period for which a reasonable assessment of needs an appetites can be made, and therefore it is essential that beyond the period of social predictability the existing buildings only suggests order and not direction. (Flexibility and adaptability are only two of the required constituents.) A short-life toy of dimensions and organisations not limited by or to particular site is one good way of trying, in physical terms, to catch up with the mental dexterity and mobility exercised by all today. Its stated and designed limited life will in itself enable the palace to be used in the particular mental behaviour pitch reserved for immensely important impermanent objects of cherished social immediacy.

Argument for Fun Palace by Joan Littlewood and Cedric Price. Presented in TDR (The drama review), vol 12, number 3, spring 1968. pp. 128

In what, from todays perspective, appears as a highly contradictious manoeuvre this system of spatial and individual freedom were to be supervised, controlled and monitored by technological programs. With the assistance of Gordon Pask the building was set up as an manipulable cybernetic field in which patterns of behaviour and usage could be experimented with, collected, processed and modelled (using game theoretical and organisational modelling syntax), as to later be fed back to the environment in what was intended to be a self-regulating and self-adjusting process. For Price the cybernetic syntax and feed-back processes were imagined to be an autonomous, unbiased and neutral system located outside of any ideological realm and providing information and adaptability as a democratised architecture in service of the individual subject and common good as such. Fifty years later the shadows of those distinctions and aspirations take on a different set of problematic colours.

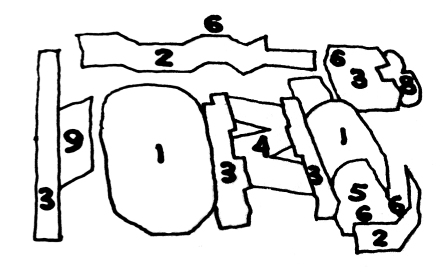

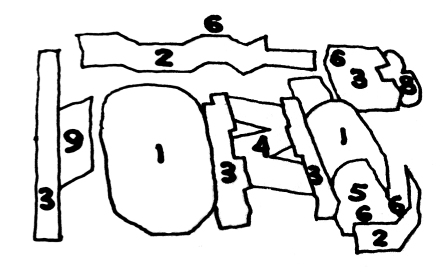

(1) Large controlled volumes for assembly, exhibitions, etc. Inflatable structure totally or partially enclosed, opaque or translucent. Free-area or containing sub-enclosuress (2) External screens providing adjustable lighting, acoustic and partial temperature control. Triodetic space frame (al.) self-supproting, capable of adjustment and re-assembly and containing heat, light and sound reflectors and baffles (3) Varied enclosures forming rooms, galleries, shelters, walkways, balconies etc. Box units with wall, floor, stair, screen, etc. Infill panels arranged as required (4) Tent roofs and awnings. Plasticized nylon tensioned sheets (5) Flooring for particular use e.g. dancing. Flooring panels direct on site surface – internal and external (6) External flood and spot lighting. Fittings capable of manual and remote control (7) External screens for film and other projections. Weather resistant braced and tensioned screen – direct and back projection (8) Mobile kitchen or other highly equipped contained services. Vans and trucks with levelling jacks (9) Horizontal or inclined barriers as 2. Capable of control by pneumatic jacks. Image/functional scheme from TDR (The drama review), vol 12, number 3, spring 1968

(1) Large controlled volumes for assembly, exhibitions, etc. Inflatable structure totally or partially enclosed, opaque or translucent. Free-area or containing sub-enclosuress (2) External screens providing adjustable lighting, acoustic and partial temperature control. Triodetic space frame (al.) self-supproting, capable of adjustment and re-assembly and containing heat, light and sound reflectors and baffles (3) Varied enclosures forming rooms, galleries, shelters, walkways, balconies etc. Box units with wall, floor, stair, screen, etc. Infill panels arranged as required (4) Tent roofs and awnings. Plasticized nylon tensioned sheets (5) Flooring for particular use e.g. dancing. Flooring panels direct on site surface – internal and external (6) External flood and spot lighting. Fittings capable of manual and remote control (7) External screens for film and other projections. Weather resistant braced and tensioned screen – direct and back projection (8) Mobile kitchen or other highly equipped contained services. Vans and trucks with levelling jacks (9) Horizontal or inclined barriers as 2. Capable of control by pneumatic jacks. Image/functional scheme from TDR (The drama review), vol 12, number 3, spring 1968

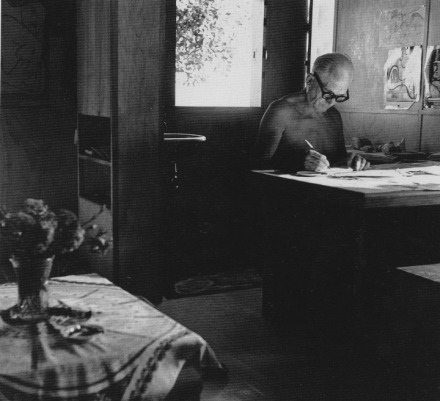

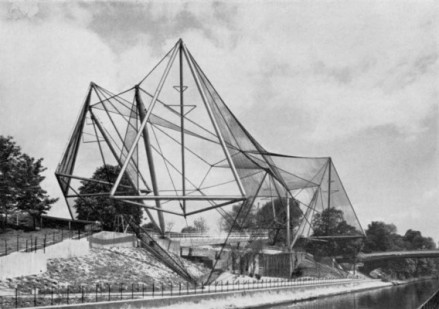

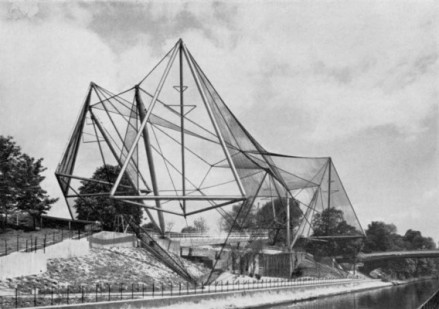

Unknown image source

Unknown image source

In the latest number of Log (vol. 23 – read the article here below) Pier Vittorio Aureli reflects on how free space has become one of the more radical manifestations of how (adaptable) labour power – “as the invisible dynamis of life” – has been exploited by capitalism; “The history of capitalist spatial governance can be understood as the possibility of accommodating the unpredictability and instability inherent to human nature.” Through the shift to a post-fordist understanding of production, space and labour, where pleasure and productivity coincides and mental and physical faculties are tangled together in an endless creation of capitalisable new and creative, the socialist ideas behind projects like the Fun Palace has been appropriated by another and radically different concept of liberating (market) freedom. And in that way an amputated legacy of the Fun Palace could be seen in the reflections of any generic shopping centre, any new university forwarding innovation, entrepreneurship and creative economy (even more true for the Potteries Thinkbelt), in the user profiling of Facebook or Google, and in the language of any contemporary art and cultural spectacle.

Hopefully our capability to apprehend, and be inspired by, the Fun Palace can transgress and address that strange development. But, to reach that level of understanding requires, as Aureli concludes, that we understand the project far better than what Price did in his own time. In all its contradictions of intent and dangerous ideological fallacies it still is a Palace of exceptionally fascinating architecture, with a potential to be reinvented as an alternative direction and a reminder of the need to liberate ourselves from our “economic function”. At the same time as Price and Littlewood made their plans for the Fun Palace, Price collaborated with Frank Newby and Lord Snowdon on the design for an aviary at the London Zoo in Regents Park (1960-63). As one of my favourite buildings, and one of only a few realised by Price, it is rather symptomatic that the passionate desire for freedom, permeability and community at the end could be described as nothing but another cage.

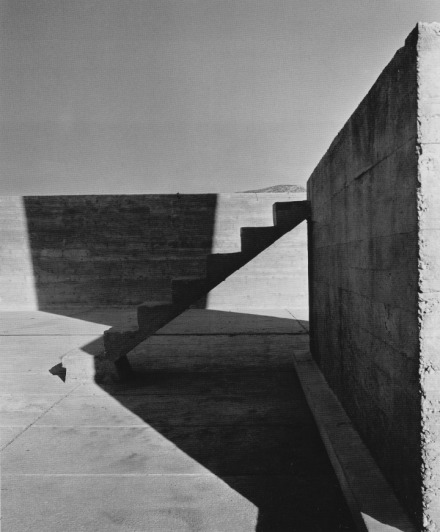

The London Zoo aviary, 1965. Image from the Cedric Price trust

Labor and Architecture: Revisiting Cedric Price’s Potteries Thinkbelt, Pier Vittorio Aureli in Log 23, 2011